Sebastian sings, in concert with the universe

Written by Masayo Fukushima

Translated by Andreas Stuhlmann

The Japanese premiere of “Kanarta: Alive in Dreams” as part of the “Visual Ethnography” program at the Tokyo Documentary Film Festival 2020 (on Dec. 9, 2020) was completely sold out, which suggests just how much attention the movie has been attracting. Director Akimi Ota had decided to make a movie on the indigenous people in the Amazon rain forest, as his doctoral work at the University of Manchester's Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology. He eventually spent over a year in Ecuador, where he lived with and filmed the local Shuar people that were once known and feared as “headhunters.” The result is a documentary film that sent shivers down my spine thanks to its innovative style of raising a variety of topics within a display of an open world-view. The following review is interspersed with parts of my recent conversation with the director.

"Come on boy!" says Sebastian Tsamarain as he cuts his path through the wild forest, captured by the camera that follows on his heels, and accompanied by the echoing sound of rhythmical breathing. Upon arriving at a plateau from where they can overlook the village, Sebastian observes the sky, and suddenly concludes that it will rain. This scene alone is charged with such a freshening sense of openness that I am immediately hooked to the exciting “story” that was about to unfold. When Sebastian sings, he sings in concert with the universe, and here I am, wondering where he is going to take me.

The “boy,” Akimi Ota recounts how he made his way to Kenkuim, a small village near the Peruvian border in central Ecuador, thanks to “a connection to a friend of a friend’s friend.” It was anything but an easy journey, and apparently it wasn’t always a safe one at that. Kenkuim is an unexplored region inhabited by the indigenous Shuar people, and it is virtually impossible for the average traveler to set foot in this area. This is where Ota stayed for an extended period of time, always having his camera ready to capture whatever was going to happen.

Sebastian and his wife Pastora Tanchima play a central role – both in real life in the village itself, and also in the movie, where they are the ones who introduce Ota to the Amazon rain forest. Pastora makes “chicha,” a unique type of liquor produced by a process that involves fermentation by chewing (comparable to Japanese “kuchikamizake”). No work gets done here without chicha, and the viewer gradually gets to understand how chicha is the very foundation that their lives are built on. In one scene, for example, we see Sebastian asking a neighbor to share some of her chicha, because his “wife was ill and couldn’t make any.” He explains that he would go and buy some, but it will be worthless if it doesn’t “taste good.” So as we watch their negotiation that is serious and humorous at the same time, we arrive at the conclusion that nothing in Kenkuim goes without chicha.

Be that as it may, I am puzzled as to how Ota managed to capture these scenes in such overly intimate, natural images. The words that describe their relationship with “Akimi” in the most direct of ways come from Sebastian and Pastora themselves. At the screening event in Quito, to which they were invited, they explained, ”Everything in this movie is true. That’s because Akimi ate any food that we gave him to eat.” After all, they would never open their hearts and minds to people who don’t eat their food. (Which shows once again just how amazing a job an anthropologist does while clearing such tricky obstacles.) They sometimes turn to the camera and directly ask it to “tell the world about the Shuar people.”

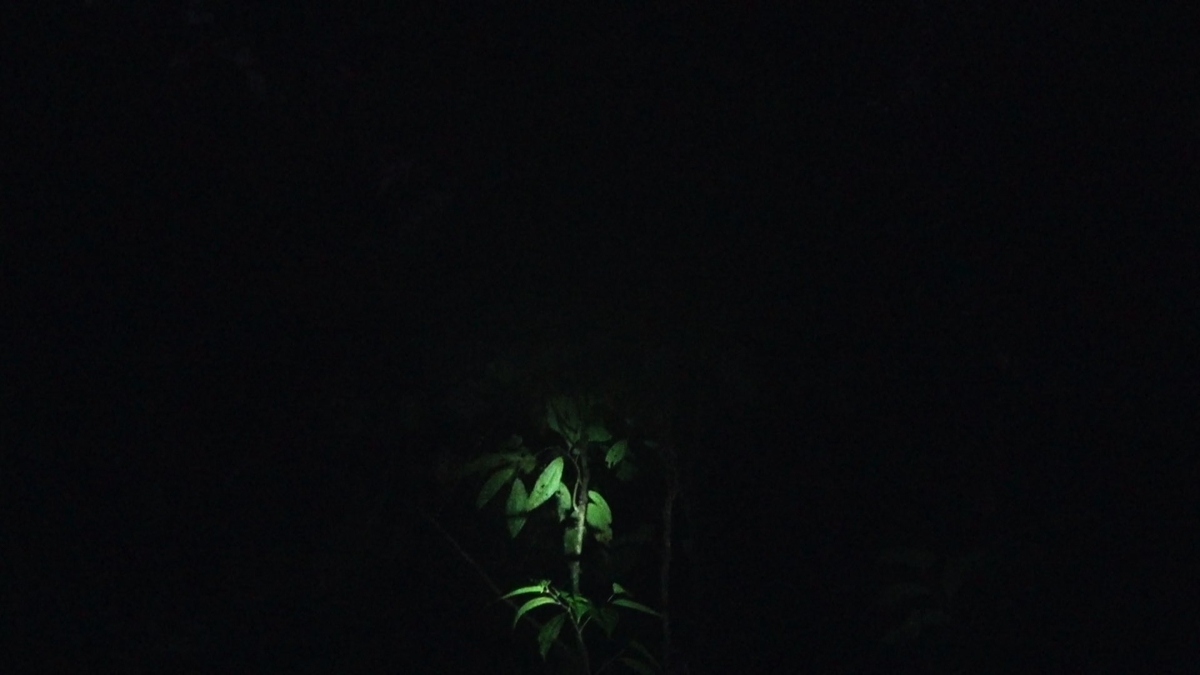

What we do not get in this movie are the typical aerial shots of the Amazon, and indigenous people in traditional costumes dancing for tourists. What is served instead is a mixed bag of trees, plants, water, earth, sky, birds, insects, and the sounds of the “inhabitants” of the forest as they continuously celebrate life with everything the abundant environment of the Amazon has to offer. A quick look at this is enough to feel that, taking a deep breath here must have an instantly refreshing effect. Equipped with a machete, they go out into the forest, which never ceases to provide things for them to eat and drink. As a matter of course, there is no Wi-Fi here. But there is a firm network through which relatives are connected. Families help each other build their houses, and watching the mothers prepare meals while chatting does feel a lot like home. It’s certainly not much different from what the typical Japanese family looked like just a few decades back. And all of a sudden, the Amazon seems so much closer...

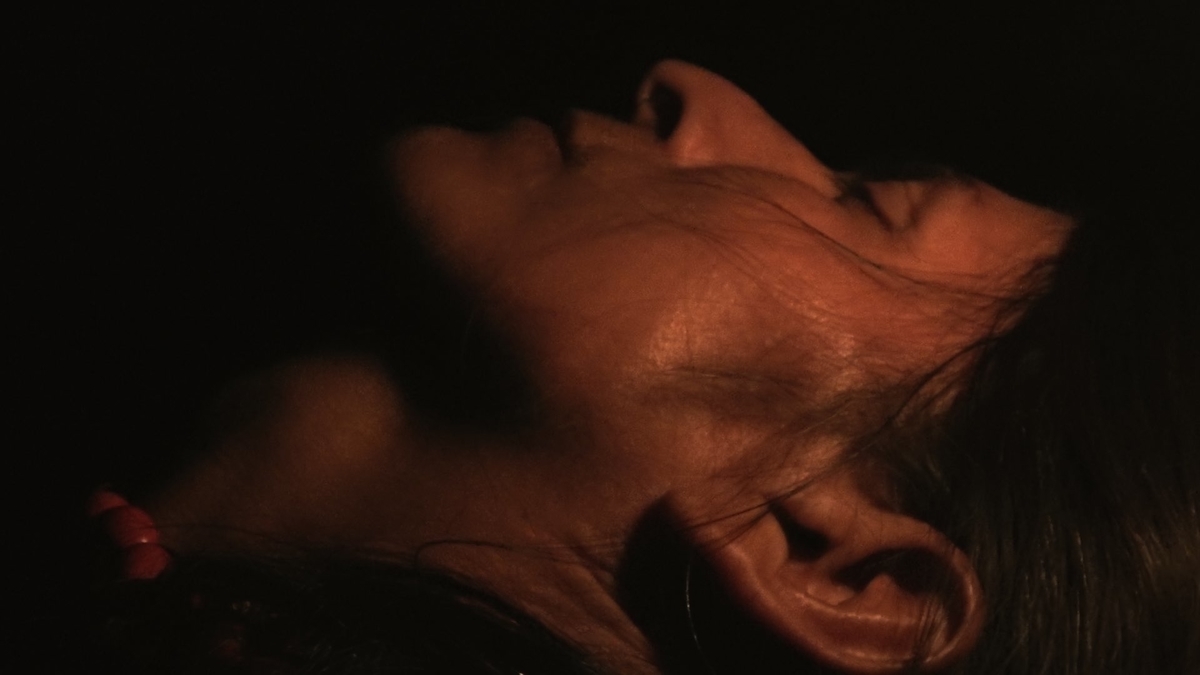

Meanwhile, the viewer is introduced to the world of medical plants, by way of the stimulating effects of ayahuasca and maikiua. Coming from a family with shaman roots, Sebastian illustrates the Tsamarains’ profound knowledge of the matter – while having a cup himself. While asleep, the body crosses the boundaries of space and time. To dream means to have a “vision.” Ota explains that he chose the (Japanese) subtitle “Rasenjo no yume (literally “spiral dreams”) because he “felt that, while adopting a circular world-view, their idea wasn’t about repeating the same thing over and over again, but they seemed to be alive in their dreams and visions that inspire each one of them to choose and pursue their own individual path in life.” Here we witness how “Akimi” himself plunges right into that spiritual experience.

“Kanarta,” by the way, reminded me of Sean Penn’s ”Into the Wild” (2007). This movie tells the true story of Chris (Emile Hirsch), who embarks on a wild journey to the north, and eventually dies a lonely death in the Alaskan wilderness. The journey in “Kanarta” takes place along the equator, and, after enduring the pains of loneliness, ends with a “safe return” in the warming arms of the Amazon rain forest and its people. The chill I initially felt running down my spine was perhaps caused by a gut feeling that I might just be witnessing a “miraculous movie.” In addition, I also heard some rather perplexing comments suggesting that it might in fact not be “Akimi Ota” who made this movie. A hint in this respect is hidden in the credits, where a certain “NANKI” is mentioned. “It would probably be impossible for me to make this movie now. I was named “Nanki” (a Shuar word for “spear” or “warrior” – referring to my courage to travel all the way alone) by the family, and it seems to me that it was that kind of ‘persona’ and power that was bestowed on me, that made me realize the movie.”

Just when I thought that, after returning from the journey with Sebastian, I would land back at the same place from where I took off, it somehow appeared to me that I was in fact on a completely different level. This surrealistically warped sense of space and time was certainly an illusion that was also triggered by a combination of cool camera work, editing and sound design, while Ota’s anthropological viewpoint worked as a filter that casually extended the visible world and the connections between people, medical care and education. This is how the movie zooms in on the wisdom of nature and how it is embraced by the rain forest people, and their lifestyle is exactly what offers a plethora of hints that mankind should take notice of if it wants to survive. I am confident that the strong, newly established ties between “Akimi” and the Amazon will serve as a vehicle that delivers the message of “Kanarta” to people around the world.

*Shuar people say “KANARTA” when they wish you to have restful sleep, good dreams and visions of what you truly are. (from "Kanarta: Alive in Dreams")

Information:

Directed, produced, filmed and edited by Akimi Ota (Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology, The University of Manchester)

Sound design: Martin Salomonsen

Colour Grading: Aline Biz

Location: Amazon Rainforest (Republic of Ecuador)

2020/120 min.

Official Trailer:

Profile:

Akimi Ota / Born 1989 in Tokyo. Graduated from Kobe University’s Faculty of Intercultural Studies (now “Faculty of Global Human Sciences”), and completed a master’s course in anthropology at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) in Paris. While engaging in anthropological investigations in Morocco and in the suburbs of Paris, he also worked as journalist and cameraman at the Kyodo News office in Paris, where he frequently visited the Cinémathèque Française. He subsequently enrolled in a doctor’s course at the University of Manchester's Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology. After spending over a year doing fieldwork in the Amazon tropical rain forest in Ecuador and Peru, in 2020 he completed his first movie as a director, titled “Kanarta: Alive in Dreams.” He holds a doctor’s degree in social anthropology. Official Site: akimi ota

Selected Awards:

- Best Documentary Feature Award, New York Movie Awards

- Best Documentary Feature Award, Florence Film Awards

- Best Documentary Film Award, Calcutta International Cult Film Festival

- Best Documentary Feature Award, Beyond Earth Film Festival

- Best Student / First-Time Director Award, Asian Cinematography Awards

Japanese review:

Tokyo Documentary Film Festival 2020 site: